How a Tiny Dot is Letting Criminals Impersonate Banks, News Sites, and the Government Online

A small, rarely used special character is potentially helping criminals trick people into falling prey to all sorts of online scams, and businesses – including some of the world’s leading media companies and financial institutions – appear to be woefully unprepared.

Here is what you need to know so that you do not become a victim

We are all familiar with the Latin alphabet, and with the fact that some characters sometimes appear with various diacritical marks above them (e.g., á and ñ), especially in non-English languages. There is, however, also a tiny dot that can appear below a character — in combination with the letters B, D, H, K, L, M, N, R, S, T, V, W, Z, and the vowels A, E, I, O, U, Y, in both upper and lower case (as Unicode characters U+1E04 through U+1EF5). On the letter n, for example, it appears as ṇ.

This dot poses a unique risk for individuals and businesses, a risk that is presently being exploited by criminals.

In an effort to create bogus websites that appear to have the URLs of their legitimate counterparts, criminals and other unscrupulous parties sometimes establish and exploit domain names similar to those that they are impersonating. They may register domains and set up phishing websites, for example, using common misspellings of the names of real banks (e.g., ciitbank.com is a site not owned by Citibank, and that clearly exploits its similarity to the bank’s name).

Crooks have also tried using the names of real sites but with one or more characters replaced with their counterparts that contain diacritical marks — for example replacing nwith ñ when establishing the domain. While such URLs may fool some people, diacritical marks above a letter stand out pretty clearly when one views a URL.

This is not the case, however, with dots below — and, for the sake of this article I will focus on the one I have seen used in a recent phishing email, ṇ, AKA n-dot.

Not only is the dot below the “n” small and sometimes indistinguishable from a dead pixel or speck of dust on one’s screen, but it is also often partially or completely obscured by the underlining commonly used to format web links in numerous applications and on many web pages. Simply put, there is a big chance that many people will not notice a small dot below a letter appearing as part of a web link.

I and others have reported this issue to several vendors, but, to this day, some web browsers, social media platforms, and applications continue to present links to sites containing n-dot (and other dotted letters) in their names without any warning or alert, and continue to regularly obscure the irregularity with underlining.

As I noted in the piece that I published last week, “Why Cybersecurity Researchers Are Suddenly Discovering the Same Vulnerabilities After So Many Years,” multiple information security professionals often suddenly discover the same vulnerability after it has gone undetected for years. The same is true for criminals and infosecurity pros. It seems that right around the time that I and several others focused on this issue, someone sent out at least one phishing email exploiting it.

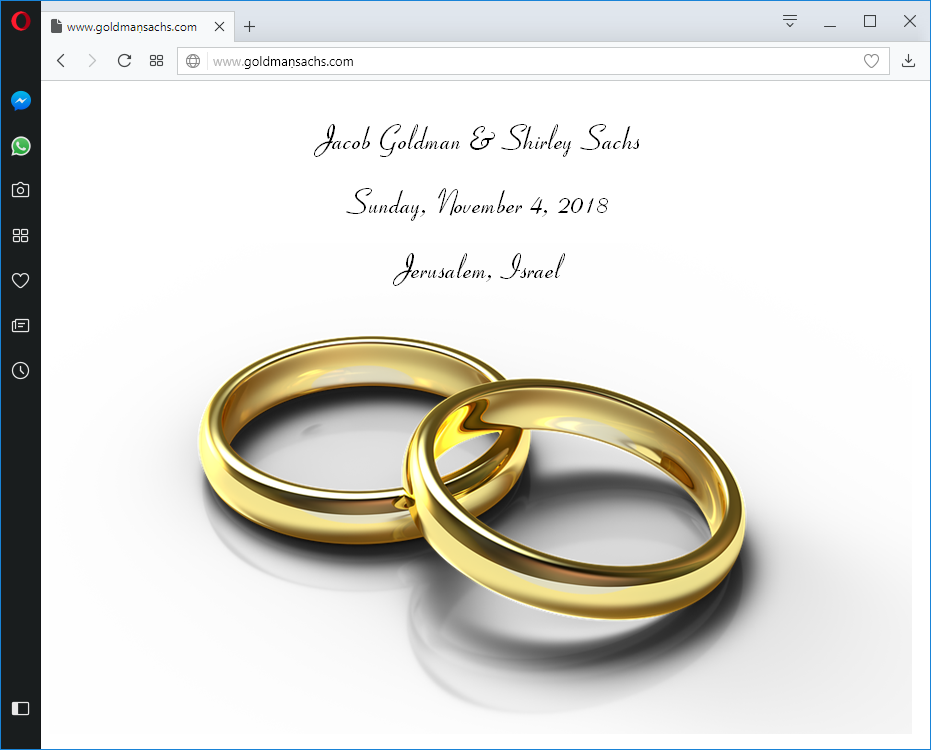

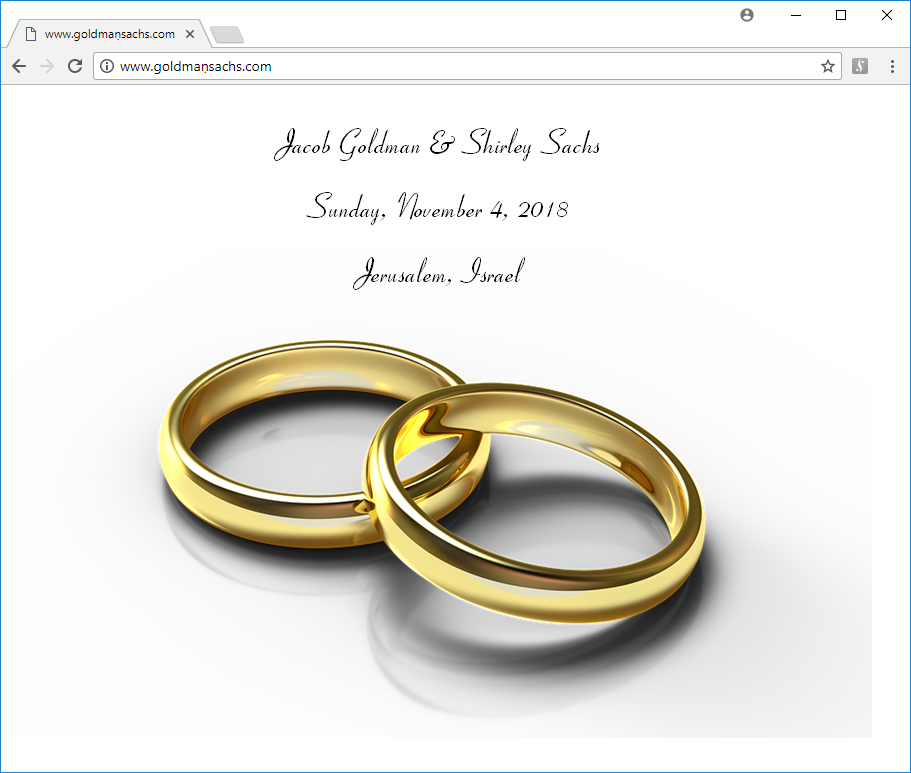

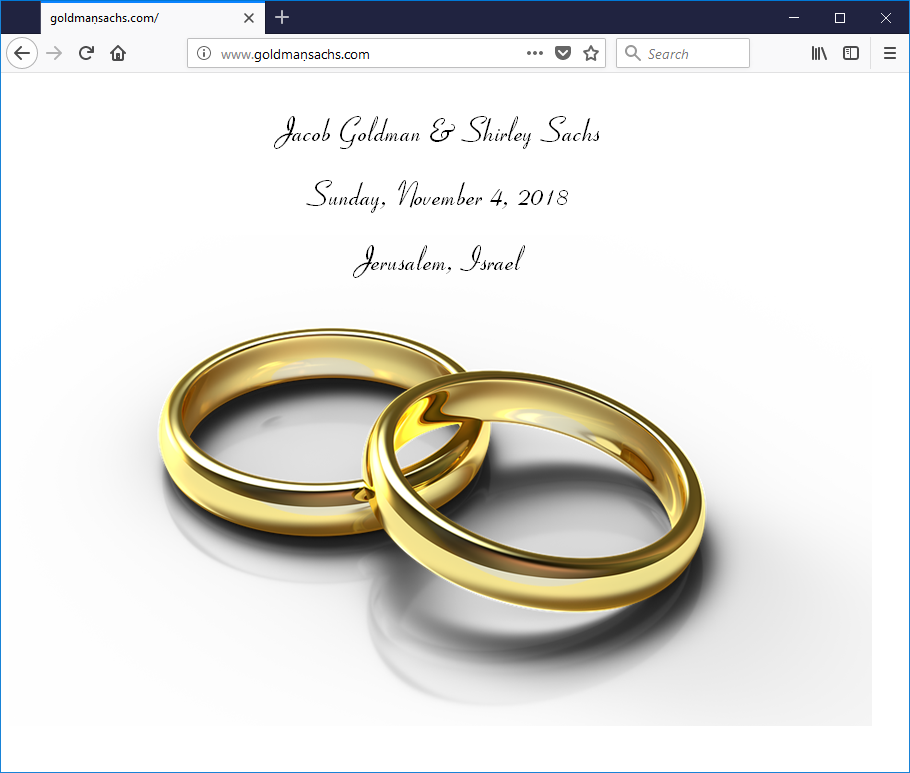

To demonstrate how dangerous the n-dot and its peers can be for users, consider the first three images below, which show a website that appears to be on a URL identical to the one belonging to the homepage of the investment house Goldman Sachs, but with the n replaced with n-dot. As it is now, this site contains a harmless wedding hold-the-date announcement, but it could have contained far more sinister material.

Opera

Chrome

Firefox

Would you notice the dot if you were not specifically looking for it?

What would have happened if a criminal started distributing links to a site with a name similar to this one, but that also mimicked the look and feel of the real Goldman Sachs site except that it also contained some bogus investment advice, or a phony password-reset feature that collected personal information as part of the reset process? How many people could have been scammed?

The same is true for fake news — unless they were told to look out, how many people would think that the following URL points to a New York Times article from yesterday about a tax reform bill? It doesn’t. (Please note: Exactly what you see below and when clicking depends on several factors including what browser you are using. I left the dot in the URL text so you can see how well the underlining obscures it, a potentially big problem on various social media platforms that display links as such. If you don’t see the dot at all you can highlight the link text to confirm that it is there.)

http://www.ṇytimes.com/2018/01/18/us/news/tax-reform-bill-vote.html

What would happen if someone spread links to a site impersonating the look and feel of a major news outlet, but that contained fake news?

Of course, the use of encrypted connections and SSL certificates should theoretically obliterate any problem of bogus sites impersonating real sites, but, as we know too well, theory is often disconnected from reality: If SSL were deployed and worked as it was supposed to, nobody would have ever fallen prey to a phishing scam.

And, of course, there are other non-standard characters besides n-dot that can be used to perpetrate similar schemes.

How should we defend against this risk?

Software vendors

There are multiple ways that vendors could address the letter-dot problem, but essentially they need to incorporate warnings of some sort if a domain within a URL contains something anomalous.

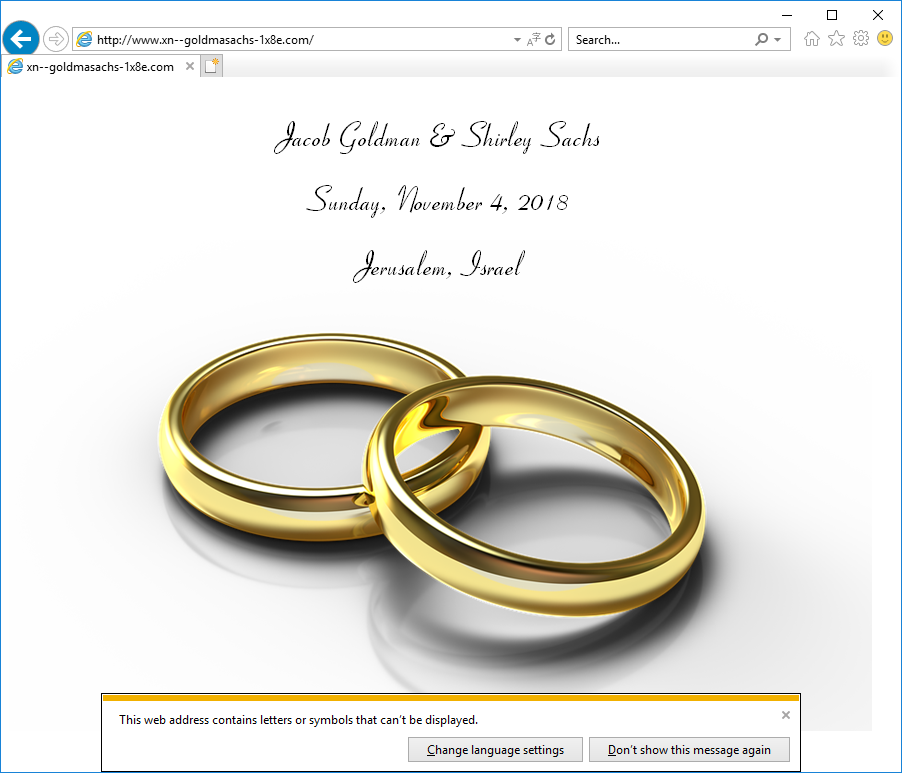

As Microsoft has done (see below), they could warn users about non-ASCII characters and display the ASCII representation of non-ASCII URLs in the URL bar. (Note: xn--goldmasachs-1x8e.com, which looks nothing like goldmansachs.com is what is sometimes called a “Punycode” representation — that is, it is a way of representing host names containing non-ASCII Unicode characters in ASCII through the use of a Letter-Digit-Hyphen combination. If you are not familiar with this concept, and visit http://www.xn--goldmasachs-1x8e.com/ in Chrome, Opera, or Firefox, you may be surprised at what you see.)

Vendors could also have an option to display both the ASCII and Unicode versions of domains, to highlight any non-ASCII characters in the domain portion of URLs, or to utilize any one of numerous other ways to draw people’s attention to anomalous domains that are in ASCII other than a small number of characters, especially if those characters are visually similar to ASCII characters.

While it is true that some vendors do display the Punycode versions of URLs if you hover over a URL, how many non-security professionals regularly check links as such before clicking them? Displaying the Punycode version of a URL after a link is clicked is also not a solution — if the bogus New York Times link redirected to a malware-distribution site instead of to my own website, users’ computers would have been infected before they had time to react.

The bottom line is that is something is “off” about the domain of a URL being accessed or linked, users should be warned in a clear, obvious, and immediate fashion.

Businesses

Businesses should also take action. When practical, as they often do for common misspellings of their names, they may wish to acquire domains that can be abused to impersonate via letter-dot characters. In any case, they should educate their users about the risks created by domain names containing non-ASCII characters, especially those containing characters that are hard to distinguish from common letters.

Businesses should also consider filtering URLs; while such an approach may not protect customers, it can help shield employees at work from accessing impersonation sites. Psychologically sound site-authentication cues (such as those that I helped invent over a decade ago at Green Armor Solutions) can also help people easily distinguish between legitimate websites and poisonous clones.

Of course, utilizing strong authentication, anti-fraud techniques, and other security measures can reduce problems if someone does fall prey to a phishing scam and compromises his or her password.

Social media monitoring technologies (including the one offered by SecureMySocial, of which I am the CEO) can also be configured to warn people if they share links containing non-ASCII domains.

Individuals

1. As I have discussed before, never click links within an email or text message.

2. If you cut and paste a visible link, check to make sure there are no dots or other symbols where there should not be.

3. Check that SSL is used and that certificates to any sensitive sites that you visit are valid.

4. Beware links on social media. If something seems amiss, it probably is. Consider who shared a link, and to where it points, before clicking it.

5. Practice good cyber hygiene in general. Doing so will reduce the chances that you will be exposed to any bad links sent by a criminal in the first place.

All in all, remember that when it comes to information security, human vulnerabilities such as the inability to notice a small dot are often more dangerous than technical vulnerabilities.

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.