US Savings Bonds Offer A Great Deal: But The Treasury’s Site To Purchase Them Offers Questionable Security

For the next few days, US Savings Bonds offer a tremendous deal for Americans seeking to park their cash for at least a year – people can lock in a rate of 9.62% interest for the next six months by purchasing inflation-adjusted type “I” bonds; a rate of nearly ten percent is several times higher than most competing ways to save money in a government-guaranteed account or instrument. (Before purchasing, of course, get the details regarding terms and conditions – for example, as related to when you can redeem the bonds and at what cost, etc.)

The rush to buy I bonds has also shown many Americans something less wonderful – that TreasuryDirect, the official government online system for purchasing and redeeming Savings Bonds, seems to employ security that is, to put it mildly, antiquated.

The system states explicitly that passwords are not treated as case sensitive, and that four special characters — < \ > . — are not allowed to be used in passwords. Such requirements weaken the security of user authentication; for the minimum 8-character passwords required by the system, TreasuryDirect’s policies reduce the number of possible passwords by somewhere around 98% – and that number only grows increasingly worse as people lengthen their passwords. More importantly, however, is the fact that because many people reuse passwords from site to site, sometimes changing only the case of one or more letters, TreasuryDirect’s policies potentially significantly increase the chances of a credential stuffing attack being successful, and of it being so before a lockout occurs due to failed password-guessing attempts.

Additionally, while, for obvious reasons, I will not explain in detail why this is so, it is possible that telling users that the specific special characters < > \ . cannot be used in passwords may give clues to hackers about potential ways to exploit vulnerabilities in the system.

Besides the case issue, there is also the matter of TreasuryDirect’s relying on security questions as part of its user authentication process; In many cases, it would seem, answers to the types of questions employed by TreasuryDirect are readily available online or can at least be quickly and easily discernable from online searches. For example, how hard is it to find out the location of someone’s dream vacation spot (one of the security questions) if that person posted at some point on a public Instagram account that they went on their dream vacation to Hawaii? Security professionals have been telling the public for many years not to utilize such challenge questions as a means of user authentication; Shira Rubinoff and I even discussed the issue in a paper entitled Key Human Factors Issues Surrounding Consumer Two-Factor Authentication and Mutual Authentication that we co-wrote over 16 years ago.

Ironically, on its Learn More About Security Features and Protecting Your Account Treasury Direct states:

If you previously chose the question “What is your mother’s maiden name?” or the question “You were born in what city?” we recommend that you consider different questions, because the answers to these are easier for others to find.

Yet, somehow, the same site continues to use challenge questions whose answers can often be found online as well – even it may take someone a few seconds longer to find them via simple searches.

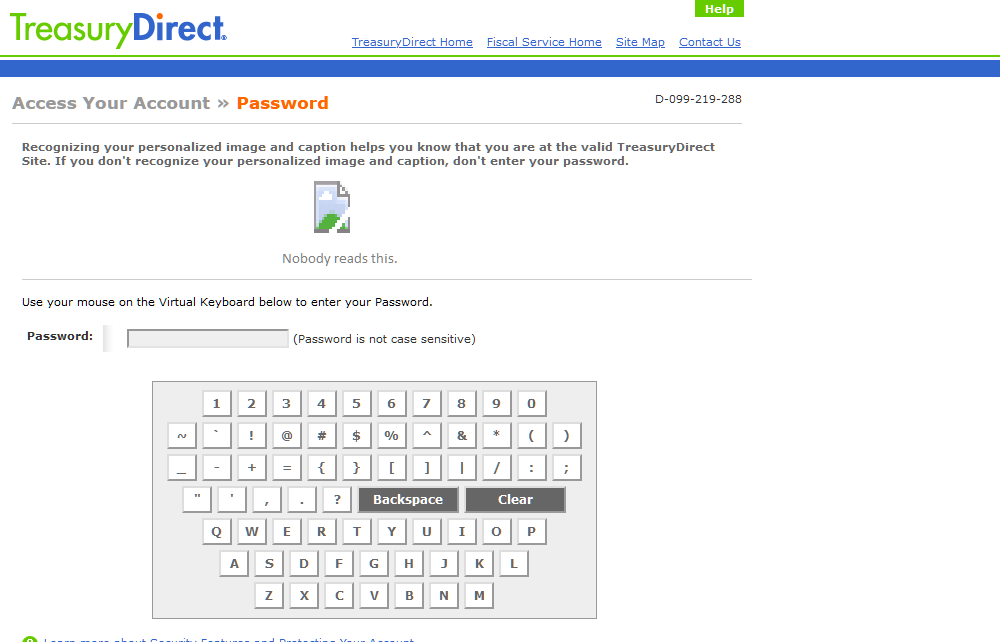

Another outdated element of TreasuryDirect’s security is its use of a virtual keyboard (with circa 1990s style keys) that requires users to click its keys with a mouse in order to enter a password. A decade ago or so such schemes were tried by various parties in an effort to defeat keyloggers, but the keyloggers quickly adjusted, for example, by incorporating technology to capture screenshots upon mouse clicks. There is a reason that you don’t see many security-conscious organizations using virtual keyboards anymore – virtual keyboards are extremely inconvenient for users and do not provide much security value anymore, if any.

TreasuryDirect also sports an image and caption to perform site authentication – a technique that was popular 16 years ago when Shira Rubinoff and I explained why such image-based site authentication is ineffective, and potentially, counterproductive; since then, however, every website that I use regularly that had used such technology in the past (including the Bank of America website among others) has transitioned to alternatives – that is, every website other than TreasuryDirect.

Of course, to be fair, TreasuryDirect does have other security features, some of which may help mitigate the potential adverse impact of the aforementioned risks.

Yet, the question in my mind remains: If TreasuryDirect utilizes such long-outdated user authentication approaches, and effectively broadcasts to the public that it does so, how well is it doing in other areas of cybersecurity?

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.