Zero Trust: What These Overused Cybersecurity Buzz Words Actually Mean – And Do Not Mean

Zero Trust.

A seemingly simple term that appears in pitches sent to me several times a day by cybersecurity product and services vendors that are seeking media exposure. And, in many (if not most cases), the term is being misused – even by the very vendors who claim to be the ones delivering zero trust to the world.

So, let’s cut through the marketing fluff and understand what Zero Trust is – and, even before that that, what Zero Trust Is not.

Despite many pitches that make zero trust sound like something that you “can buy for $19.99 if you call now”:

• Zero Trust is not something that any one product can deliver to you.

• Zero Trust is not something that any one vendor can deliver to you.

• Zero Trust cannot be purchased off the shelf even from a combination of vendors.

• Zero Trust is not something that you can achieve overnight.

So, what is Zero Trust – in layman’s terms?

Zero Trust is a concept, an approach to information security that dramatically deviates from the approach commonly taken at businesses worldwide by security professionals for many years. From a practical standpoint, implementing a Zero Trust approach requires a major transformation in many ways; achieving zero trust is, therefore, a process or a journey – not a have or have-not destination.

Historically, organizations implemented security using some form of “castle and moat” model in which the digital perimeter of the organization was heavily defended, but, computers located inside the of the “castle” were deemed to be trusted insiders. In many cases, there were, of course, multiple layers of “moats” and multiple discreet “castles” – but the devices located on the same network segments were still trusted by one another. There may have also been the equivalent of guards inside the castle – intrusion detection systems to detect anomalous activity, for example, and DLP systems to monitor what parties seeking to exit the castle were carrying with them, etc. – but, in the end, users of devices were trusted because the devices that they were using were connected to an internal network. The reasoning was simple, since only trusted parties could connect to those internal networks, parties on those networks should be trusted.

Such an approach seemed straightforward, but, even in the past, it was far from perfect; today, not only does such an approach not fully work, it is severely problematic.

Remote workforces, cloud applications and storage, the use of smartphones and other devices not under organizational control (BYOD), modern cyberattack techniques, hardware and software components sourced from around the world, vulnerabilities in Internet of Things devices, and various other practically-speaking unchangeable realities have both individually, and in combination with one another, rendered the “castle and moat” approach at best obsolete, if not downright impotent.

Consider the case of ransomware, for example, and the fact that the number of successful ransomware attacks has skyrocketed in recent years. If a user sitting at a computer connected to an internal network falls for a social engineering scam (something that has, statistically speaking, already happened many times during the time that you have been reading this article), and, as a result, inadvertently infects his or her computer with ransomware, if that device is trusted by other devices on the internet network, the ransomware stands a good chance of spreading like wildfire throughout the network. (In actuality, wildfire is not even a good example, because ransomware can actually spread orders of magnitude faster than wildfire!)

Zero Trust is an approach to address this big-picture problem.

Zero Trust states that nothing is trusted – and certainly not based on the location in which it sits or from which it came – every single request for a resource must be properly authorized, and that applies whether a request is made by a human using a device or a device on its own. Furthermore, authorization should only be granted if a party asking for access to the resource actually needs access to that resource for a legitimate purpose (AKA adopting a true need to know basis).

Effectively, Zero Trust assumes that organizational networks may be breached at any time, so, in order to minimize exposure, no resources should ever be provided to anyone or any device unless the party asking for them proves that he/she/it is authorized to receive access, is authorized to do so from the device and network from which the request is being made, and needs such access. Obviously, implementing a Zero Trust approach requires that organizations truly understand in detail what they actually have in place, from both a hardware and a software perspective. They must also understand their business processes down to a granular level. And, of course, they must know, and be able to strongly authenticate, any human users as well.

Because adopting a true Zero Trust approach requires so many changes beneath the hood of how organizational systems interact, achieving Zero Trust requires robust planning in advance of implementation – ad hoc efforts are exceedingly unlikely to deliver what is needed. I will discuss in a future article what roadmaps should contain in order to be most likely to yield successful Zero Trust adoption efforts.

This post is sponsored by VMware.

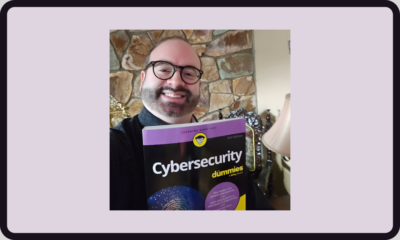

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.

CyberSecurity for Dummies is now available at special discounted pricing on Amazon.

Give the gift of cybersecurity to a loved one.